Why I Changed My Mind on Baptism

Here are the key findings that hammered the nail into the proverbial coffin of my credobaptism.

I began my foray into the reformed world on a steady diet of R.C. Sproul. By the time I was serving as a full-time church planter I had consumed far more than my fair share of Ligonier resources—ravenously devouring each video as though it would be stolen from me. Somewhere along the way, I realized that every theologian I read and almost every pastor I listened to was opposite from me on the issue of baptism. This realization dawned on me over the course of several months and I dealt with the topic by declaring a kind of cease-fire. There would be no reading or thinking related to the topic of baptism for the near future, I had a church to plant. But I was unable to avert the topic forever.

That cease fire came to an end through the providential hand of God. There were two things that happened which really shook the foundations of my credobaptistic beliefs.

The first was the conversion of a good friend to paedobaptism. I had been discipling him about all things calvinism and trying to get him to see the beauty of that system of doctrine. He went away for a weekend trip with some homework listening (the “Chosen By God” series on Ligonier). When I saw him the following Wednesday he casually said “I’m all the way there.” As I began to crack a smile he added, “...even the babies”. My initial gloating turned quickly to shock as I said, “No brother, you’ve gone too far!” As he and I talked over the coming years he consistently exhorted me to look at the evidence and study, so I assured him that I would once I found the time for it.

The second event took place about a year later while taking a Hebrew class at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. My professor, Dr. Duane Garrett, assigned us some bonus reading for the course—a new book that he had written called The Problem of the Old Testament. In that book, with all my suppressed baptism questions lurking in the shadows, I read the line, “The New Covenant is not like Sinai. The Old Covenant is broken and set aside. Discontinuity, not continuity, is the distinctive feature of the New Covenant.”1 Every part of me rebelled at this approach to the Old Testament, and quite frankly, this book sent me over the edge.

For the next year I set out to study the topic more earnestly now that I could no longer hide from it, but deep down I knew that my mind was already made up. Here are the key findings that hammered the nail into the proverbial coffin of my credobaptism.

The Relationship Between the Scriptures

The first issue I had to settle was the basic relationship between God’s work in the Old Testament and the New. How can we best understand the unfolding plan of God from beginning to end? This is the bedrock issue.

If the Old Testament is for Israel under the Old Covenant and the New Testament is for the Church under the New Covenant, then there is little carry over from the Old Testament into the life of the Christian today.

If, on the other hand, the New Covenant is the maturation of all the covenants that God made with man, then there is much we can learn as Christians from these older texts. The Old Testament carries weight as we seek to understand morality, righteousness, and most importantly, how we understand redemption. In particular, how God works in Genesis will be how we expect him to work in Acts.

So then what does unite the corpus of Scripture together? The great binding agents in all of Scripture are God’s character and covenant. The narratives in the Pentateuch are built around his covenants and the exhortations of the prophets call his people back to them. Even the New Testament is organized in this way, for God’s covenantal salvation comes into its full focus through the life of the Lord Jesus Christ. He is the one who inaugurates the New Covenant right before he is betrayed—something each of the Synoptic Gospels explicitly mentions. As O. Palmer Robertson says, “Christ took on himself the curses of the covenant and died in the place of the sinner.”2

In all my searching I concluded that God has always had one plan of salvation, organized around his covenantal activity, which has now come into its fullness in Christ. While this did not resolve the issue of whom to baptize, it did narrow the playing field quite a bit. Now that I was solidly covenantal, I only had two paths before me: I had to evaluate the reformed and reformed baptist claims concerning how this New Covenant sign is to be administered.

The ‘Newness’ of the New Covenant

As I spoke to some trusted pastors and professors about my baptism debacle, I was regularly told I needed to read Dr. Steve Wellum’s argument in Baptism and the Relationship Between the Covenants. To a man, everyone said this was the definitive defense of believers baptism from one of the top reformed baptist scholars today. Dr. Wellum asks, ‘What is “new” about the new covenant? What is the main difference, if any, between the older and newer administrations of the covenant of grace given the basic continuity of the covenant?” He answers, “most covenant theologians view the “newness” of the new covenant in terms of a renewal rather than a replacement.’3

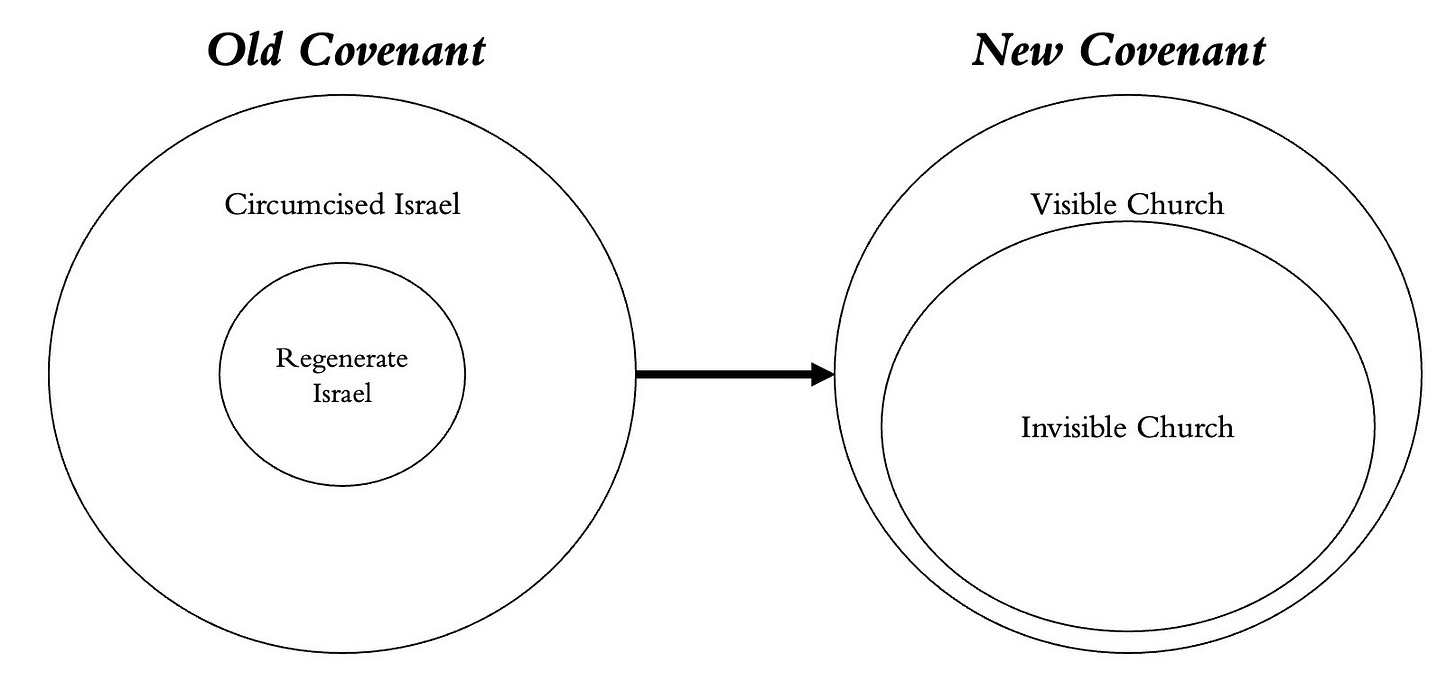

This is the classic view. The New Covenant community is a mixed people, comprising both regenerate believers and false professors. It could be illustrated as:

Dr. Wellum outlines the shortcomings of this view by rejecting the Visible and Invisible church distinction.

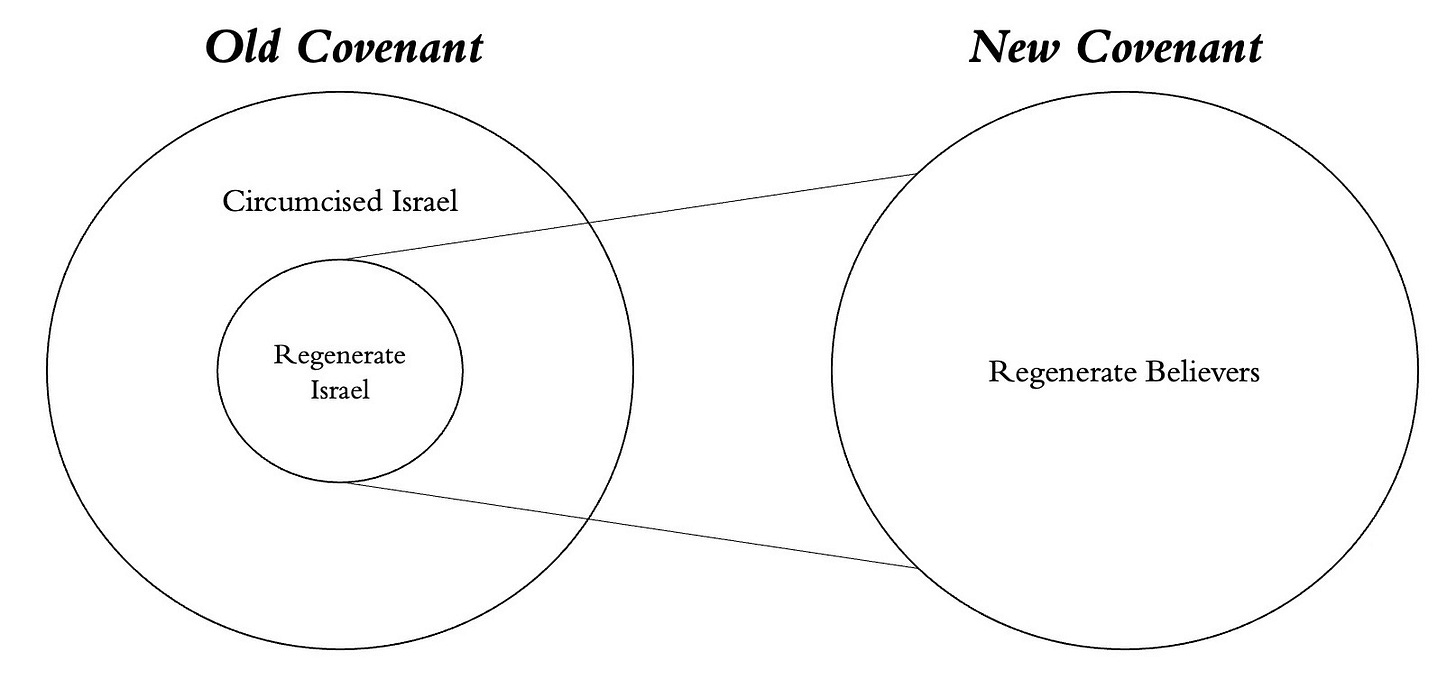

But covenant theology’s discussion of “newness” fails to reckon that in the coming of Christ the nature and structure of the new covenant has changed, which, at least, entails that all those within the “new covenant community” are people, by definition, who presently have experienced regeneration of heart and the full forgiveness of sin (see Jer 31:29–34). Obviously this view of “newness” implies a discontinuity at the structural level between the old and new covenant—a view which is at the heart of the credobaptist position—but which covenant theology rejects.4

So according to Dr. Wellum the “newness” of the New Covenant looks like this:

Here are a smattering of quotes that will underscore that point.

“Because the church, by its very nature, is a regenerate community, the covenant sign of baptism must only be applied to those who have come to faith in Christ.”5

“That is why in a Baptist view of the church, what is unique about the nature of the new covenant community is that it comprises a regenerate, believing people, not a mixed people like Israel of old.”6

And my personal favorite comes from Mark Dever who says, “Christ’s glory is most displayed in the church when baptism guards both the regeneracy of church membership and the consistency of the church’s corporate witness.”7

But we must ask the question, can Baptism actually do what the reformed baptists claim it can do?

The Meaning of Baptism

Baptism is indeed the sign of the New Covenant, but the New Covenant is not by nature a regenerate community. This is impossible. Dr. Wellum asserts that “Baptism, which is the covenant sign of the new covenant church, is reserved for those who have entered into [union with Christ] by the sovereign work of God’s grace in their lives.”8 But how can we know who is regenerate and who is not?

My baptist friends will say we should only baptize those with a credible profession of faith, because that will guard the regeneracy of the church, but even those with credible professions may apostatize later (1 John 2:19; John 15:6). I will not rehash all of the warning passages, because Tim has already written about a few of them, but anyone who recognizes that people do walk away from the faith will find themselves on the horns of a dilemma.

If people can apostatize, even after being baptized, then it follows that the New Covenant is not by nature a regenerate people. But if people cannot apostatize, then why are there so many warnings about it in the Bible and so many examples in real life?

Rather, the New Covenant people are, as the Old Covenant people were, a mixed community, who will have tares among the wheat. So our preaching reflects that of Moses, for even to a gathered congregation of Christians a pastor must say, “Circumcise therefore the foreskin of your heart, and be no longer stubborn” (Deut. 10:16; cf. Jer. 9:26; Acts 7:51). And need I any more proof of this than the warning: “Take care, brothers, lest there be in any of you an evil, unbelieving heart, leading you to fall away from the living God” (Heb. 3:12)?

None of this threatens the meaning of baptism. Because it is still a sign and seal of union with Christ, and for those who fall away, it is a witness against them of their apostasy.

How We View our Children

So then we come to the final, and I think most heartfelt, part of this whole discussion. I am not, after all, a brain floating in a vat that thinks about theology, but I am a husband and a father. Towards the end of my thinking on this topic my wife and I discovered we were expecting our first. This took an academic concept and turned it very quickly into a practical one. How do I view my child?

Well I could at this moment turn to the many passages where entire households get baptized, but I think I could more succinctly put together my thoughts in a quote.9

One time, while observing Presbytery exams, I saw a candidate being asked about baptism and what it means. As he was working through his answer Dr. Kris Holroyd asked him a striking question, “When your child is sitting across from you at the dinner table, do you see an Israelite or an Amalekite?” And for me there was no question at all.

Children of believing parents are considered believers until the time they prove themselves to be false. We preach the gospel to them, we exhort them to repent from their sins and trust in Jesus, but our motivation is not because we think they are outside his people. I regularly teach my boys to pray to Jesus and to sing songs about Jesus because they are his people and he is their God.

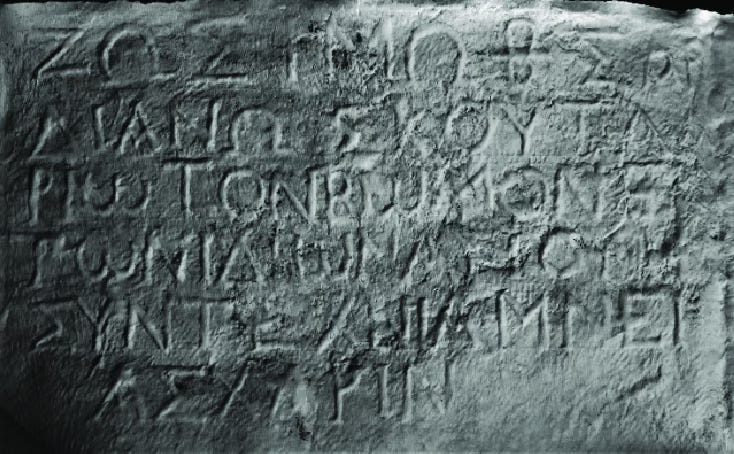

And there is ample evidence that Christians in the early church thought this way about their children as well. A famous inscription exists which details the burial of one early Christian by the name of Zosimus. We know nothing of Zosimus besides the following words about him, “I, Zosimus, a believer born of believers, lie here having lived 2 years, 1 month, and 25 days.”

For as long as there have been Christians, they have viewed their children as part of the faith. They have raised them in the faith. They have trusted that God’s covenantal promises to a thousand generations would come to pass, and in keeping with that covenantal thinking, they have baptized their children and taught them diligently to observe the words of their God.

Duane A. Garrett, The Problem of the Old Testament: Hermeneutical, Schematic, and Theological Approaches (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2020), 118.

O. Palmer Robertson, The Christ of the Covenants (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing Co, 1980), 12.

Stephen J. Wellum, “Baptism and the Relationship Between the Covenants,” in Believer's Baptism: Sign of the New Covenant in Christ, eds. Thomas R. Schreiner and Shawn D. Wright (Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing, 2006), 104.

Stephen Wellum, “Baptism and the Relationship Between the Covenants,” 138.

Stephen Wellum, “Baptism and the Relationship Between the Covenants,” 138. Emphasis mine.

Stephen Wellum, “Baptism and the Relationship Between the Covenants,” 113. Emphasis mine.

Mark Dever, The Church: The Gospel Made Visible (Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing, 2012), 148. Emphasis mine.

Stephen Wellum, “Baptism and the Relationship Between the Covenants,” 113.

For the household baptisms in the New Testament see: Cornelius (Acts 10:24); Lydia (Acts 16:15); The Philippian Jailer (16:31–33); Crispus (Acts 18:8); and show that Stephanas (1 Corinthians 1:16). Also consider 1 Corinthians 10:1–2 where several hundred thousand Israelite children are baptized.